The 6th Bomb Group

A Typical Mission

Target and Mission Selection

|

Over time, mission distances increased significantly. Many missions lasted 15 hours - which is a long time to spend in any airplane. The emergency runways at Iwo Jima were a lifesaver. The longest mission was the July 11 mining mission to Rashin, Korea. Only one plane - "Here's Lucky" from the 39th Squadron - flew the entire 4,000 miles non-stop. This took 19 hours and 40 minutes, at an average speed of just over 200 mph. That may have been the longest bombing mission of the entire war. (On June 26, a plane from the 39th Bomb Group flew the longest combat mission of the War, from Guam to Hokaido - 4,650 miles in 23 hours. However, that was a reconnaissance flight.) |

|---|

Selection of Crews and Aircraft

Pre-Mission Maintenance

While the crew tried to get a good night's sleep (or day's sleep if the mission was at night), the ground crews were busy trying to get the plane ready for the mission. Their overall goal was to keep as many planes flying as possible- which was hard when the air crews kept bringing the aircraft back with holes in them. Nevertheless, the ground crews knew that the entire success of the air campaign lay in their ability to get enough planes in the air to make a mission.

If the aircraft was flyable, the ground crews had to load the aircraft with the precise mix of fuel, bombs and ammo. Too much, and the aircraft would crash on takeoff. Too little fuel and the aircraft would not return. Too little ordnance and the trip would have to be repeated. |

|---|

Pre-Mission Briefing

In the hours immediately preceding the mission, the air crews received their briefings. There were also separate briefings for the different aircrew. For example, the navigators went to a separate briefing that concentrated on navigational information that they would need. Once the briefings were done, the crews boarded trucks for the trip to the airfield. |

|---|

Transport to the Flight Line

Following the briefing, the crews hop into waiting trucks for transport to the flight line. |

|---|

Preflight Procedures

One of the standard preflight procedures was to pull the props through. This was done to help lubricate the upper cylinders and to avoid buildup of oil in the lower cylinders. This buildup could cause hydrostatic lock which could destroy an engine. Pistons are designed to compress air, not fluid. Since fluid is not compressible, pushing against the fluid would result in a bent piston rod, or worse. (Sometimes, though, worse is better. A blown head gasket would probably be noticed before takeoff. A bent piston rod might not be noticed until after takeoff, when it is discovered that the engine is not developing full power.) If there is fluid in the cylinders, pulling the props through will not eliminate the fluid. Instead, the spark plugs should be removed to allow the fluid to drain out. However, it was discovered that the fluid could also be flushed out by pulling the props through backwards. Unfortunately, this did not necessarily eliminate the fluid, but merely pushed it into the intake manifold. Once the engine was started, the fluid could return and create hydrostatic lock. However, pulling the props through backwards was a quicker procedure.

So, this is a risk that people sometimes took- just one of many. |

|---|

Takeoff Procedure

The 6th Bomb Group parking area was at the southwest part of the airfield. Presumably, each of the 3 squadrons would occupy a taxiway. The aircraft scheduled to participate in the mission would exit their hardstands forming a line at the end of the runway. Because of the tendency of the engines to overheat, the crews would follow special procedures in taxiing to the runway. Initially, the crew would taxi using only the two inboard engines. Once the airplane was lined up behind another airplane, and receiving a cooling blast, the crew would switch to the two outboard engines. When they were a few places from takeoff, they would restart the inboard engines. The planes would take off in 30 second intervals. This meant that, with luck, a squadron of 16 planes could take off in 8 minutes - which is quite a while if the aircraft want to fly to the target together. If the 6th Bomb Group was the only group flying the mission, they could shorten the time by using additional runways. However, this was not always possible on maximum effort missions, since other groups would be using the other runways.

|

|---|

In Flight

On a typical mission, the airplane was so heavy that the crew had to fly the airplane for several miles in "ground effect" a few feet above the ocean. Once the crew has burned off enough fuel, the weight was low enough to enable the aircraft to climb a few thousand feet. They would not climb to the mission altitude until just prior to reaching the target area. In contrast with Air Force practice over Europe, the planes did not form up and fly in tight formation all the way to the target. Instead the planes flew in loose formation. There are several reasons:

Where the mission involved other wings and groups, the sky would be full of B-29s. A 500 plane formation could extend for more than 100 miles.

|

|---|

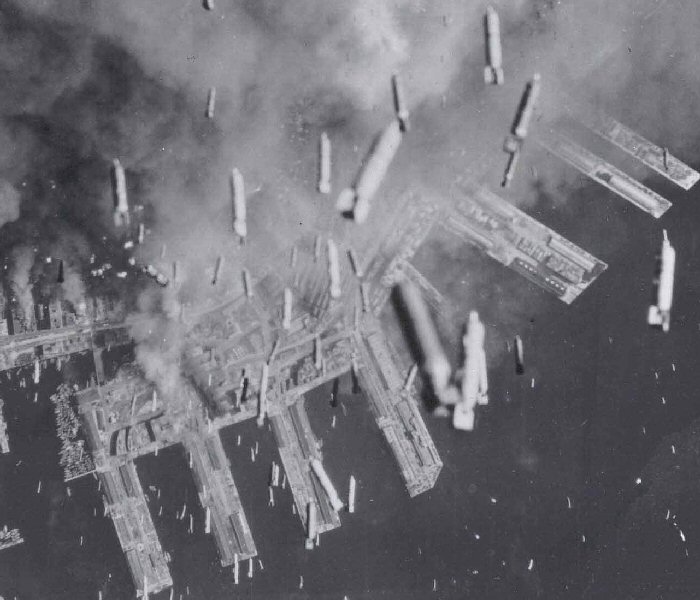

Bombs Away

After a 6 hour flight, the aircraft would finally be able to drop their bombs on target. If they were lucky, there would be no flak or fighters to greet them. If the target was visible, they would drop the bombs visually. If the target was overcast, they would use radar to try to identify the target. Once completed, the aircraft would turn around and fly another 6 hours back home. Rest and repeat.

|

|---|

By the end of the war, a crew had to complete 35 missions before they could return home. At 3,000 miles per mission, that works out to a total of 105,000 miles. This is over 4 times around the world (24,900 miles) or almost halfway to the moon (238,857 miles). This was accomplished at the blazing speed of 200 mph with an overloaded semi-reliable aircraft and people shooting at you. |

Landing

|

|---|

Post Mission

After the mission, combat crews were transported back from their aircraft to the Group housing areas where they were debriefed and received refreshments from the Red Cross volunteers. |

|---|